In most American cities these days, it seems like there's a Chinese restaurant on every other street corner.

But in the late 1800s, that ubiquity was exactly what certain white establishment figures feared, according to a new study co-written by Gabriel "Jack" Chin, a law professor at the University of California, Davis.

Chin examined how white union workers and lawmakers waged a nationwide "war" on Chinese restaurants in America from 1890 to 1920. "It shows this tradition of an expectation on the part of some white Americans that public policy should be organized for the benefit of their employment," says Chin, who adds that he sees parallels with anti-immigrant policies being put forth today.

In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred Chinese immigrants from entering the U.S. for decades. Some white Americans worried that Chinese laborers would steal their jobs and hijack their opportunity.

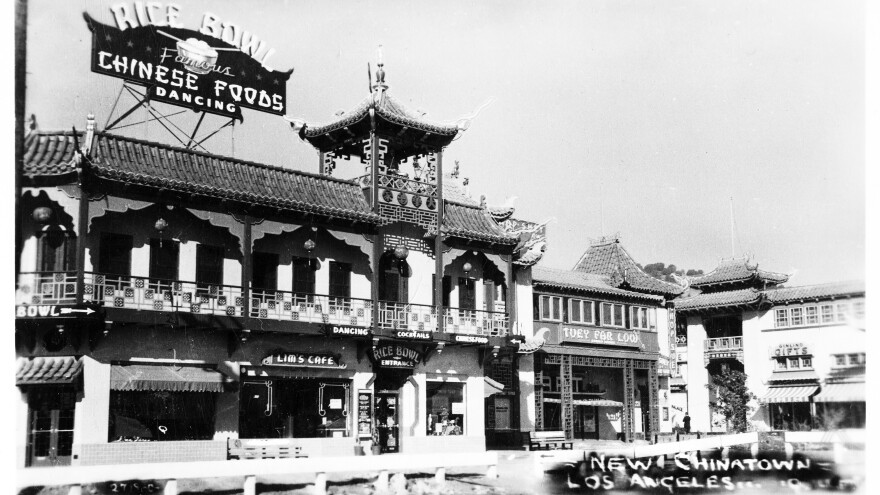

And this xenophobic fear carried over to the restaurant industry. Chinese restaurants — known by some at the time as "chop suey houses" — were understood to be a good value, offering inexpensive meals in an exotic setting.

"The economic menace [of Chinese restaurants] was twofold," says Chin. "First, if Chinese people had the opportunity to earn a living, then they might stay. And their communities would continue to exist, and the Chinese presence, which many objected to, would continue."

The second thing, says Chin, is that "if Chinese restaurants made Chinese food available at a relatively low price and then American restaurants wouldn't be able to compete, either the wage scales for American restaurants would have to go down or they would close."

And then, there was the pervasive idea that Chinese men were lecherous threats to white women. Chinese restaurants were considered "dens of vice," Chin says, where white women were at risk of moral corruption by way of sex, opium and alcohol.

I talked with Chin about his research and how anti-immigrant sentiment can manifest itself in even the most "creative" of methods. He told me about six different ways that Chinese restaurants were targeted:

1. Race riots

There were Chinese communities expelled from Western and Mountain States through race riots, Chin says, where Chinese restaurateurs or miners were beaten or quite literally burned from their homes.

2. Boycotts

Unions representing cooks, waiters and bartenders organized largely unsuccessful boycotts against Chinese restaurants in many places, including Massachusetts, Arizona, California, Montana, Minnesota and Ohio. The unions imposed fines on union members who ate at Chinese restaurants, Chin says, but couldn't keep their members from eating there: "Individual members of the public had incentives to cheat because the food was understood to be a good value at the time."

And, Chin points out, for the most part, these unions weren't trying to enlist Chinese restaurant workers to join their ranks. Instead, they were vying for Chinese employees to be replaced by white workers.

3. A peculiar law

When boycotts were largely unsuccessful, the unions turned to the legal system. At the American Federation of Labor's 1913 convention, organizers proposed that all states should pass laws that barred white women from working or patronizing Chinese or Japanese restaurants for both moral and economic reasons, Chin says. (A similar law had been enacted in Saskatchewan, Canada, and upheld by Canada's Supreme Court.)

States including Montana, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Washington and Oregon saw versions of the bill, which were ultimately unsuccessful. In Massachusetts, for example, the state Supreme Judicial Court struck down the law on the grounds that it was discriminatory.

4. Government agencies and licenses

Chin points to old newspaper reports that show that government agencies refused to issue business or restaurant licenses to Chinese restaurateurs, citing various reasons: Some officials claimed they had already issued enough licenses. Others said they would not issue licenses to people who were not citizens. And since Chinese people couldn't naturalize, this targeted them.

5. Policing

While the proposed white women's labor law was never officially enacted, some police officers began patrolling the restaurants of their own volition, Chin says. "We see newspaper reports," he explains, "where the police in the first decades of the 20th century believed they had the authority, and exercised it, simply to issue orders in the public interest." For example, he adds, "when there were concerns about white women patronizing Chinese restaurants and when the police thought this was prejudicial to the safety of white women, they would simply order white women out."

In 1909, the murder of a prominent white union leader's daughter by a Chinese restaurant worker inflamed tensions. In June of that year, Leon Ling reportedly strangled Elsie Sigel in a jealous rage and stuffed her body into a trunk in his bedroom. Sigel had met Ling when she worked in Manhattan's Chinatown as a missionary, and her death and the subsequent manhunt for her killer sparked a wave of racial profiling across the country.

Newspapers hyped the story, with headlines like "Was Strangled By Her Chinese Lover: Granddaughter of General Sigel Slain in the Slums of New York." The case seemed to justify the fears that union workers had of all the misfortunes that would spring from Chinese restaurants. "To be a Chinaman these days," one Connecticut newspaper wrote, "is to be at least a suspect in the murder of Elsie Sigel."

6. Banning private booths

Private booths were little rooms where customers could dine; they were often found in Chinese restaurants. But in 1917, the United States Public Health Service published a model ordinance that prohibited private booths, Chin says. Some people campaigned to get rid of them, "because in chop suey restaurants and other restaurants, nefarious things could happen behind the curtain." This was a way to specifically target Chinese restaurants.

While Chinese restaurants were able to weather these affronts from the unions — Chinese restaurants even surged in New York City during this time because of a loophole that allowed small-business owners visas into the U.S. — Chin argues that enough damage had been done. The anti-Chinese viewpoints of white labor unionists helped solidify the notion that Chinese people were both economic and moral threats to white Americans and paved the way for the passage of the Immigration Acts of 1917 and 1924, which more broadly restricted the immigration of people from all Asian countries.

It wasn't until there was a dramatic drop in Chinese immigrants in the U.S. that union organizers began to ease up on their targeting of Chinese restaurants.

"The issue wasn't Chinese restaurants per se," Chin says. "It was: What if Chinese restaurants grow and grow and drive out American restaurants — then what?"

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.