Heroin use in King County is at epidemic levels. Government and public health officials say something needs to be done. So, they’re forming a task force. While some question whether "coming up with an action plan," as county officials put it, is the quick response the crisis warrants. Officials say the task force will result in a coordinated, broad-reaching effort aimed at reducing overdose deaths. According to King County Public Health, in 2014, there were 156 overdose deaths in in the Seattle-King County area from opioids, including heroin. That's the highest ever recorded.

What will the Task Force do?

The task force; which will be made up of representatives of public health, law enforcement and researchers; will look at ways to provide addicts with a variety of options when it comes to seeking help.

Adrienne Quinn directs King County’s Division of Community and Human Services. She says one possibility is to provide family doctors with treatment tools.

”We would like to engage the primary care medical community and provide treatment within primary care settings. Some people will seek treatment that may not otherwise seek it in other settings and it will be more accessible,” said Quinn.

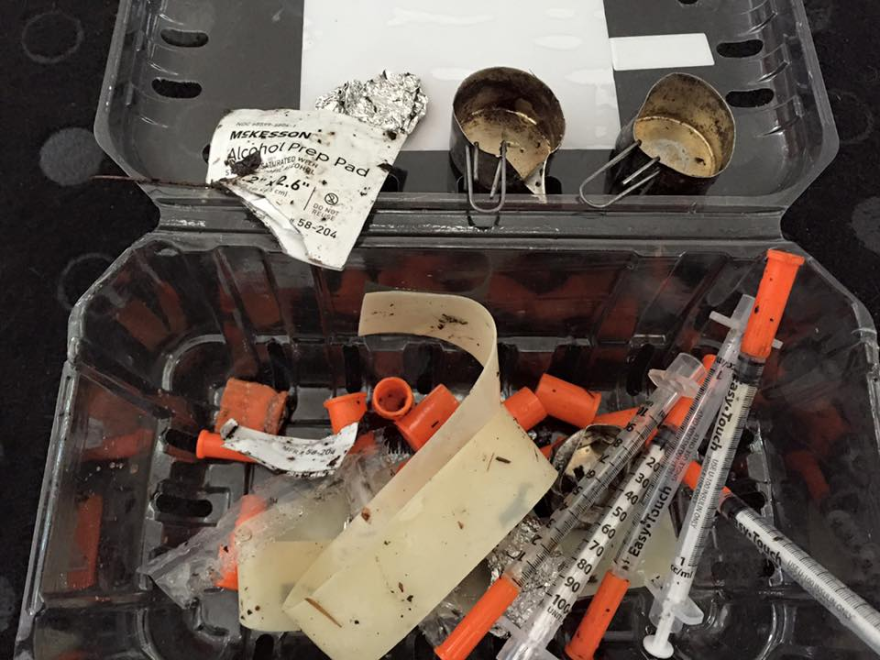

The heroin task force will also consider such controversial measures, such as providing safe drug injection sites for addicts. The goal, King County Executive Dow Constantine says, is “harm reduction” in whatever form it takes.

A Personal Story

At a news conference to announce the formation of the task force, Thea Oliphant-Wells stood next to local dignitaries. She had a personal story to tell and, through that story, she also had suggestions for officials trying to tackle the heroin problem.

“Ten years ago, I was homeless and addicted to heroin,” Oliphant-Wells told reporters.

She says she started using as a teenager and was given the drug by an uncle who was already an addict. She says one thing people who intend to address this problem need to consider is the stigma that's associated with shooting heroin. She says it plagued her interactions with a lot of people she went to for help.

“The shame of my existence was ever present. Those who helped me most on my road to recovery were those who did so without judgement,” she said.

Something else to keep in mind, she says, is the need for safe and affordable housing for people trying to get clean.

“Many of us ... address our healthcare concerns while living in a tent or a car or a doorway,” she said.

Most importantly, Oliphant-Wells says she wants to dispel a common misperception about addicts.

“That old saying 'once a junkie, always a junkie' is a lie. Opiate addicts can and do recover,” she said.

Oliphant-Wells sees herself as living proof. After kicking her habit, she went to college, got a masters degree and now works as a social worker in King County’s needle exchange program.