As new data shows overdose deaths fell across the country last year, health care providers are still rushing to help people using fentanyl and other drugs.

In Washington state, some addiction specialists are working to make treatment more accessible — especially for those who are dealing with homelessness and other issues.

The Emergency Mobile Opioid Team in Everett, or EMOTE, drove through the Snohomish County community on a recent morning – looking for anyone who is unhoused and may need help.

The street medicine team’s medical director, Dr. Tom Robey, stopped to check on Kaylee Roquet. She has been staying in a cramped motel room with her dog and is about eight months pregnant. On top of all that, Roquet is also dealing with serious medical issues like high blood pressure and an infected leg wound.

She tells Robey when he visited that she had not been feeling well the past few days. The doctor tries to convince her to check into a hospital that could treat her and help with her opioid use. Roquet says she can’t right now, but asks, "Could we look at [my baby]?”

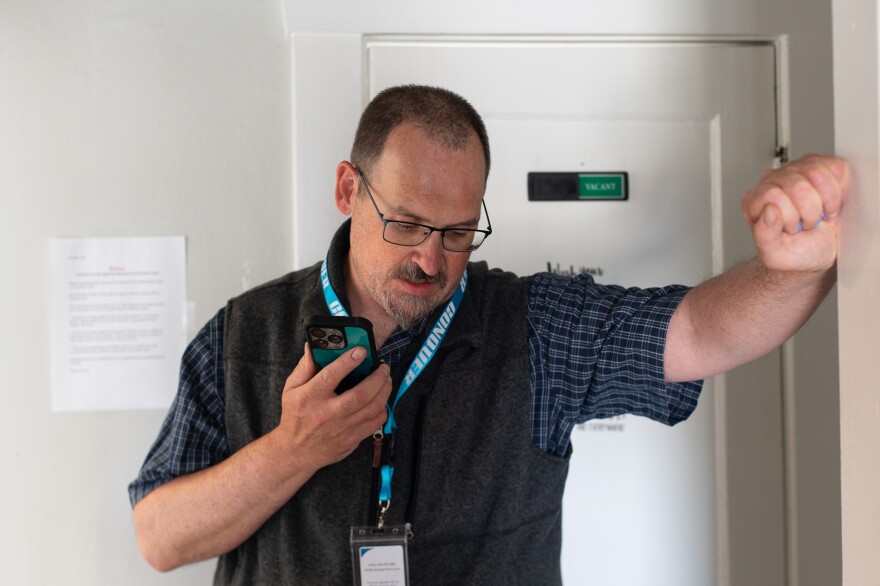

Robey says yes and pulled out a small ultrasound kit to start the procedure. Looking at the imaging displayed on his phone, he says, “The baby is in a better position this time. Ok, so there is an arm and we follow it down and there’s the little hand."

Roquet is excited to hear about her baby and asks the doctor to take some ultrasound photos.

This checkup is a part of EMOTE's effort to provide compassionate medical care to people and make it easier to access addiction treatment in Everett. However, Robey barely mentions drugs to Roquet. His priority isn’t pushing sobriety – it’s making sure his patients feel comfortable while providing the care they want.

That can span helping someone experiencing withdrawals or just making time for a conversation. Robey said treating someone can span giving them a “bottle of water [or] some encouragement. Sometimes they might need help connecting to treatment and then sometimes people need medical attention.”

It may sound simple, but being respectful can go a long way towards helping someone struggling with drug addiction. According to Caleb Banta-Green, a researcher who studies addiction and how it’s treated at the University of Washington, a lot of people using drugs have had terrible experiences seeking out medical care.

“They need to be comfortable coming out of the shadows, they need to be comfortable going to a care site that’s actually going to treat them well and kindly,” he said. “Most people with active substance use disorder, when they go to seek care they're generally shamed, told they are lying and they are often told to go away.”

Earlier this year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released new findings that it claimed showed the agency's efforts to help communities prevent fatal overdoses have been productive.

According to data released in May, the CDC estimated that there was about a 27% decline in overdose deaths across the U.S in 2024 from the year before. The main driver of those deaths was the potent opioid fentanyl.

The agency stated in a press release that this is “a strong sign that public health interventions are making a difference and having a meaningful impact.”

The CDC noted that despite this improvement overdoses are still the leading cause of death for Americans between ages of 18 to 44. Banta-Green says this data may have dark implications since the number of fatal overdoses have spiked in recent years.

“At some point you have to peak and start coming back down and you’re coming back down because so many people have already died,” he said. “We're still at an astronomical high level of overdose deaths.”

Washington state lagged behind the nation and, at the time of this reporting, only saw about a 10% decrease in overdose deaths last year. It’s estimated more than 3,000 people died from an overdose in 2024 and there are signs that deaths are on the rise again across the state.

According to Banta-Green, to effectively curb the number of opioid overdoses treatment medications like methadone and buprenorphine need to be easier to find. Over the last ten years, he’s been working to help make that possible.

“What we’ve been working for the last decade in Washington state to build is a community based model of care where anybody can go on on a drop in basis to get access to treatment medications,” he said. “It’s building a bunch of pop up clinics.”

There's been bipartisan legislation to create these kinds of facilities across the country, but so far that initiative hasn't gained momentum. However, healthcare providers in Washington are still dedicated to providing this style of care.

Over the last year in Everett, Conquer Clinics - which operates EMOTE - joined forces with the Sound Pathways Harm Reduction Center to create a health engagement hub. These two organizations’ are working to provide medical and behavioral health services along with addiction treatment in one location.

The health engagement hub is a place where a person can walk in to get an injury patched up, grab a clean syringe, eat a snack, sign up for health insurance or get help with their substance use.

Jessica Thornton manages the harm reduction center at the hub, which has operated a needle exchange in Everett for years. Thornton didn’t originally work here though, she first started coming here while she was actively using drugs. She remembers how kind the staff was and what that meant to her.

“It lit me up as a human being able to walk in through these doors cause there was no expectation of me and I was treated like a human being,” Thornton said. ”I was able to be touched and hugged and somebody asked me how my day was and it didn’t revolve around my drug use.”

Thornton is no longer using drugs. She said having healthcare providers located on site with the harm reduction center has been huge. It makes it possible for her staff to build relationships with individuals - then introduce them to a doctor or nurse at the urgent care clinic just down the hall.

She said they slowly “build that trust and it can be as simple as [asking], ‘Hey, the doc’s in today, would you like to see them?'"

The health engagement hub in Everett is able to provide health care to patients largely because of grant funding and because many of their patients qualify for Medicaid. The federal - state program that provides health insurance to people with low-income or who have a disability.

Right now though, Republican lawmakers in Congress are rushing to pass President Trump's contentious tax legislation known as the "One Big Beautiful Bill, which would change how Medicaid is administered and cut federal spending for the program.

This bill would also affect federal healthcare programs like Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act marketplace.

Democratic lawmakers like Washington state U.S. Senator Patty Murray worry this legislation will be devastating. She said this will be devastating for the nearly 2 million Washingtonians their insurance through Apple Health, the state's name for its Medicaid program.

In a statement this week, Murray condemned Trump's proposal in response to the Senate narrowly passing a version of the bill — sending it to the House of Representatives for consideration.

“Republicans’ legislation will mean 17 million Americans will lose their health insurance, including more than 328,000 people in Washington state who rely on Apple Health and Affordable Care Act coverage," she said.

Banta-Green believes these cuts could be hard on people in recovery. He said if someone loses their health insurance and “can’t be on treatment medications that means they are at an extremely high overdose risk — I mean that is just the bottom line.”

He worries some may turn to fentanyl if they don’t have the proper medicine to help them deal with their opioid cravings and withdrawals.

Back in Everett at the motel room, Dr. Tom Robey is sitting by Kaylee Roquet as he finishes up her ultrasound. Roquet is excited to have her baby. She wants a boy, but she has a feeling that she's going to have a daughter.

As he's wrapping up, Robey reveals to her the baby's sex.

“Well, there's the little butt, in between the little butt there does not appear to be an extra little part," he said. "So, I’m still gonna hedge, but I think your suspicion that it’s a girl is spot on.”

After that Robey packed up and headed off to his next patient. He said Roquet delivered her baby earlier this month in a hospital.

Robey treats patients out on the streets with EMOTE and at the health engagement hub. He’s not sure how the potential cuts to Medicaid could affect the effort to help some of the most vulnerable people in Everett. He said it could reduce the number of patients he can treat, but at this point, he doesn’t want to focus on that because it’s not productive.

“I'm still going to come to work, and I'm still going to try to convince pregnant patients to go in and get care,” he said.

He's plans to continue treating wounds and trying to get his drug addicted patients off of fentanyl because that’s all he can do at this point.

Robey hopes what he and his colleagues are doing at the health engagement hub and with the street medicine team is helping prevent people from dying from a fatal overdose.