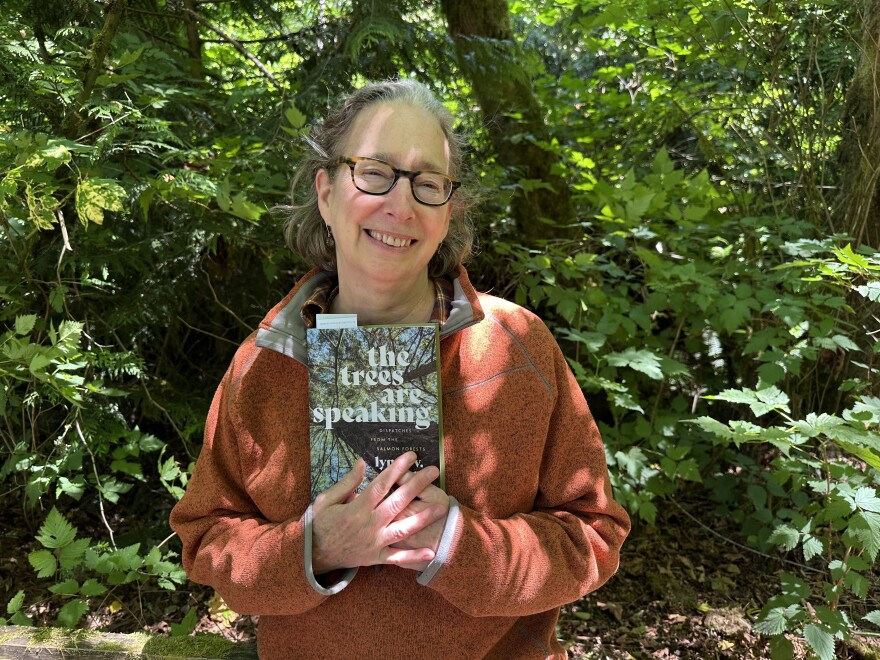

Environmental writer Lynda Mapes, who recently retired from The Seattle Times, has a new book.

It’s called The Trees are Speaking: Dispatches from the Salmon Forests. It’s a follow-up of sorts to her last book, Witness Tree – which was about a single oak tree, facing climate change.

This one is about the future of forests.

In part one of our series, The Understory, KNKX environment reporter Bellamy Pailthorp went to meet Mapes in one of Seattle’s great forests, to learn more.

Click “Listen” above to hear their conversation, or find the transcript below.

Transcript

Note: This transcript is provided for reference only and may contain typos. Please confirm accuracy before quoting.

KNKX Environment reporter Bellamy Pailthorp: Lynda, we are here in Carkeek Park in North Seattle. I know chum salmon return here every fall. Is this what you would call a salmon forest?

The Trees are Speaking author Lynda Mapes: 100%. What's going on here is this beautiful exchange of nutrients from the great pastures of the sea all the way to these inland forests. These forest streams bring these beautiful, silvery fish to the land from the sea, and they feed these trees. It's incredible to me that when I talk to scientists, you know this term salmon forest is not just a saying, it's a scientific fact.

You can see, for instance, the Adams River in B.C. turns into just an absolute salmon highway in the big return years, and scientists can see a change in the color of the canopy, Bellamy – from space. It turns darker green, brighter green because of all the nitrogen and nutrition coming back in the carcasses of those salmon. And if you core into a tree, you can see fatter rings, bigger rings, more growth in a year when there's been a big salmon return.

So salmon forests really are exactly that: the trees provide the cooling to the stream that the salmon need for their birth houses, their roots hold the soil to prevent erosion, and they provide the cool, clean water by holding that water in the soil and retaining it in the aquifer that the salmon need too. So the trees help the salmon, and the salmon help the trees. It's a beautiful reciprocal relationship, which, if allowed to, will go on forever.

Pailthorp: And you went all over the place for this book. You spent a lot of time here in the Pacific Northwest. What was a main takeaway from all of that travel?

Mapes: What this is about is commodification. It's the displacement of the original knowledge systems of this place, of the first people about living in reciprocity, in a relationship with the forest for multiple generations, where the money is kept, not in some distant bank for investors, but it's kept in the living community of the forest for the non human beings as well as the human beings. And generation after generation, this is a place of wealth and abundance and sustenance for the people and for the non human beings.

That was all displaced with the arrival of the colonizers, who, when they first came to the northeastern tip of North America, could not believe the forests that they encountered. These were wood famished people, and they quickly set about cutting it all down and proceeded to move across the country, and it's still going on in B.C., where old growth, 1000 year old trees are still being cut for mere commercial products.

So this arrival, this displacement of the original knowledge and management systems of these forests, that's what this is about, turning these forests not into anything that you're trying to sustain for the future, but into mere profit.

Pailthorp: How do we get away from that, especially with our modern lives, where we, many of us, are addicted to wood? I mean, you described yourself, I heard at one point as a wood hog. We like wood. We want it in our lives.

Mapes: It's so true. I am a wood pig. I confess. I live in a house built of wood in 1916 in Seattle, which means, you know, you look at the trim and it's made from old growth wood. There's just nothing else that could be that big and thick and beautiful. I write at a desk made from Douglas fir. I write with a pencil on paper. I work in a newspaper. I write books. So I love wood, I use wood, I burn wood.

But here's the thing I wish for us, two things: Number one, a change in our relationship with nature, that we think about nature with a sense of respect. These are complex places that cannot be simplified to mere commodities. And so what I wish for us is that we would listen to that and not let just mere profit be the guide or commodification, or, for that matter, ever increasing use, without any thought as to what we're doing to these natural systems. Second homes, third homes, paper plates, paper napkins — no thought whatsoever as to where that's coming from, or, for that matter, the people doing the work we need to do for forests, what we've done for food.

And really think about this as a local movement of respect, reverence for trees and for forests. And to really think about where these products come from, the people who produce them, what do we truly need? What can we do without and how do we steward these places for the long haul? There are examples of people doing this now, both tribes and also non-Indian producers of products and people who work in the woods.

I looked at one particular nonprofit in Maine. I was very excited about what they're doing. This is the Appalachian Mountain Club. It's an outdoor club for heaven's sakes, and they are buying land with donations, and they're using it in three ways. One-third gets set aside for permanent wilderness, just no human intervention. Another third is used for recreational access. After all, that's what they're about. The third chunk is logged, but it's logged in a way that's meant to improve the condition of the forest. Take the little ones, leave the bigger ones to get bigger.

So there won't be any one answer to this. These have to be local solutions by local people that make sense in local places. But they are happening, and that gives me hope.

Pailthorp: And this is not just about logging, as you write.

Mapes: To me, at this point, logging is almost quaint, at least we can turn that on or off or up or down. We're also talking about hot drought and fire and bugs that the forests that we have created and the climate that we have created cannot coexist.

The trees are speaking. They're telling us that we are in a situation now where, even in protected areas, we're losing old growth and mature trees, and we're losing them not to the chainsaw, but to insects and blight and drought and heat and fire. You know, we have to get serious about changing our policies to accommodate the reality of climate change.

Pailthorp: Lynda, you've spent several years now focused on trees. Why? Why are you so interested in trees these days?

Mapes: I would say that I want people to appreciate the wonder that is a tree. I mean, here's a being that can be in one place for centuries, and not only not deplete it, but make it better by providing homes for so many animals, so much wildlife, providing the fresh air that we breathe. Every third breath comes from a green plant, sustaining the water, cleaning the air, cooling the air, providing solace for humans. If we didn't have trees, we would need to invent them.

Pailthorp: Lynda Mapes, Seattle Times writer and the author of...how many books now?

Mapes: Six!

Pailthorp: Six books now. Thank you so much for your work.

Mapes: Thank you, Bellamy. It's a pleasure.