In December, sunflower sea stars were declared critically endangered by an international union of scientists. This species is the largest and hardest hit among the iconic and colorful starfish that have been devastated by a wasting syndrome.

Over the past seven years, the epidemic has caused sea star populations to plummet up and down the west coast, with heart-wrenching effects: literally dissolving them as they shed their limbs and gradually disintegrate.

But there is hope. Pockets of healthy populations of sunflower sea stars still exist in parts of the Salish Sea. And a scientist working at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Labs on San Juan Island is pioneering new techniques to breed them in captivity.

The goal is to learn what exactly is killing them and someday boost their populations by learning enough to safely release them back into the wild. But first, the researchers need to gather certain key information.

"We're trying to understand basic aspects of their life cycle,” says marine biologist and etymologist Jason Hodin, the lead researcher on the project.

“For example, how long-lived are they? How long would it take them to recover their populations and grow from embryo stage to adult? There was literally zero information about that for the species.”

And no one had any experience raising them in a lab. So, Hodin had to figure out everything: what kind of conditions to hold them in, from the amount of flow and natural scum kept in the tanks, to what to feed them.

“I mean, we didn't know any of that,” he says.

They started with several thousand embryos on their first round and tried dozens of combinations in different tanks. From that initial foray, he now has 14 juvenile stars that he is raising in Friday Harbor.

And Hodin now knows what they like to eat.

“Mostly clams. Clam juveniles that we got from Taylor Shellfish,” he says, adding that his crew raises the tiny clams to feed his baby sea stars now, along with algae for the juveniles and experimental sea urchins.

“We're basically a multi-level aquaculture – small-scale operation,” he says.

And he has 29 adult sunflower sea stars that they captured from the waters around San Juan Island for the breeding program. Their preferred food is mussels – shell and all.

“We feed them like one large-sized mussel or two medium-sized mussels every two days,” he says. “They swallow the whole shell and then spit out the empty shell.”

They’re voracious predators, which is one of the reasons there is so much concern about their demise in the wild. Their absence has led to a surge in urchin populations in many areas, which in turn has caused a decline in large kelp forests. Entire ecosystems are shifting.

After they were captured, each adult star was given a name by whoever caught them for the lab. Hodin says he named quite a few, based mostly on their appearance.

“Like, I named one Prince because it kind of has a purple hue. And I named one Van Gogh after – it reminds me of a sunflower from a Van Gogh painting. And Clooney has kind of gray hair,” he says.

But Hodin says he also notices the adult stars have personalities and something like intelligence. They have “learned,” their tender says, what it means when the cover of their tanks is lifted and left off: It’s feeding day.

“They will come up to the surface and expose their undersides to be fed. And some of them are do that kind of thing more than others,” he says. “They have certain behaviors or places in the tank where they like to hang out, stuff like that. There's no doubt that they have some degree of personalities that we're just kind of getting to learn.”

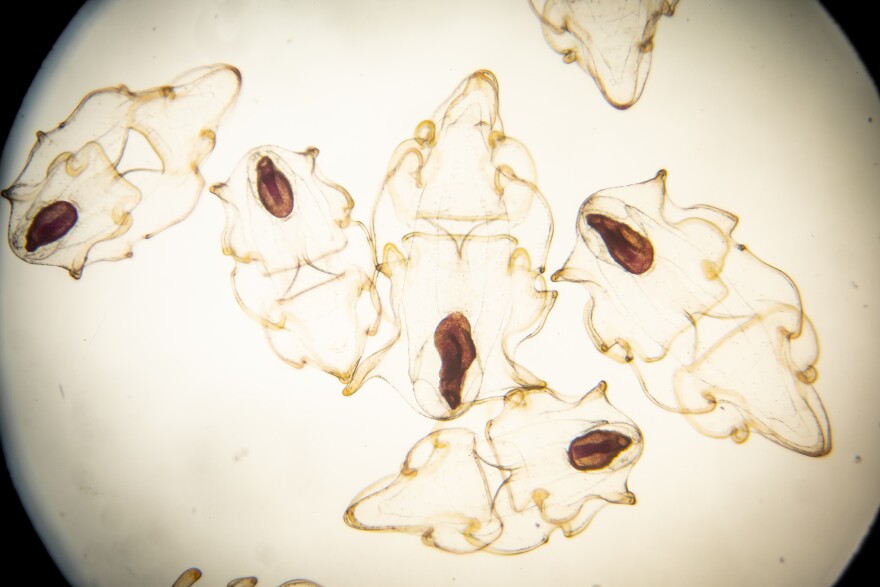

Likewise, Hodin has learned from hours spent looking through the microscope, at how the minuscule embryos flow around, “settle” and gradually morph into baby stars.

Metamorphosis is a process he had studied extensively in the insect world. He says watching the sea stars make their transition is has left him amazed and in awe.

His lab assistant describes the shape of the tiny embryos seen under the microscope as being something like H.P. Lovecraft’s fictional monster Cthulhu.

“And they do look like that a little bit. They have these really, really long, flexible arms that that they weave around in the plankton,” Hodin says.

“And they wave them up in the water column, too. So it's not clear what they're doing, but they may be sort of like sampling the local environment that they attach down in.”

Hodin uses the word “decide” for what they do after apparently sampling the water column and then attaching themselves to the substrate, eventually growing into baby sea stars.

He has also seen them regenerate their limbs and is collecting some of the first data on the rate at which that happens. He thinks it typically takes two to three years for an adult to grow back an arm fully, so that it can’t be distinguished from the rest of its body.

And he says there are several other experiments they’re working on, many of which give him real hope for a revival of the species. Chief among those is a study on the sensitivity of the sea-star larvae to temperature. It has never been studied before, and Hodin says they’re finding them surprisingly resilient and robust.

“We've been raising them at cool temperatures, and that's not anywhere near their optimum,” Hodin says.

He says their optimum temperature appears to be 17 degrees Celsius, or about 63 degrees Fahrenheit.

“That's warm for around here. We don't get water temperatures up to that level except in tide pools in the middle of the day,” he says.

That experiment is one he looks forward to carrying out with a new round of juveniles. He is also refining the techniques to optimize the growth of his sea stars in captivity and get more than 14 through the reproductive process.

“You know, to see whether you can produce them in numbers that might eventually even be reintroduced into the wild at some point – if that seems wise to do.”