In 1986, Miles Davis released the album Tutu, dedicated to Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

Davis had only recently returned to performing after five years of silence. To re-establish himself as the ever-changing chameleon of jazz, Davis teamed up with 27-year old bassist and producer Marcus Miller, and they chose a political theme for their project.

Miller remembers that, at the time, South Africa was the foremost thing on his mind. He said in a 2012 interview, “All our eyes were on the struggle against apartheid.” He wrote the title track, “Tutu.”

“I wrote the song because I was reading about Desmond Tutu and his work, and at the time, we were mostly hearing only about Nelson Mandela,” said Miller. “So I wanted to highlight Bishop Tutu too because my grandfather was also an Episcopal bishop.”

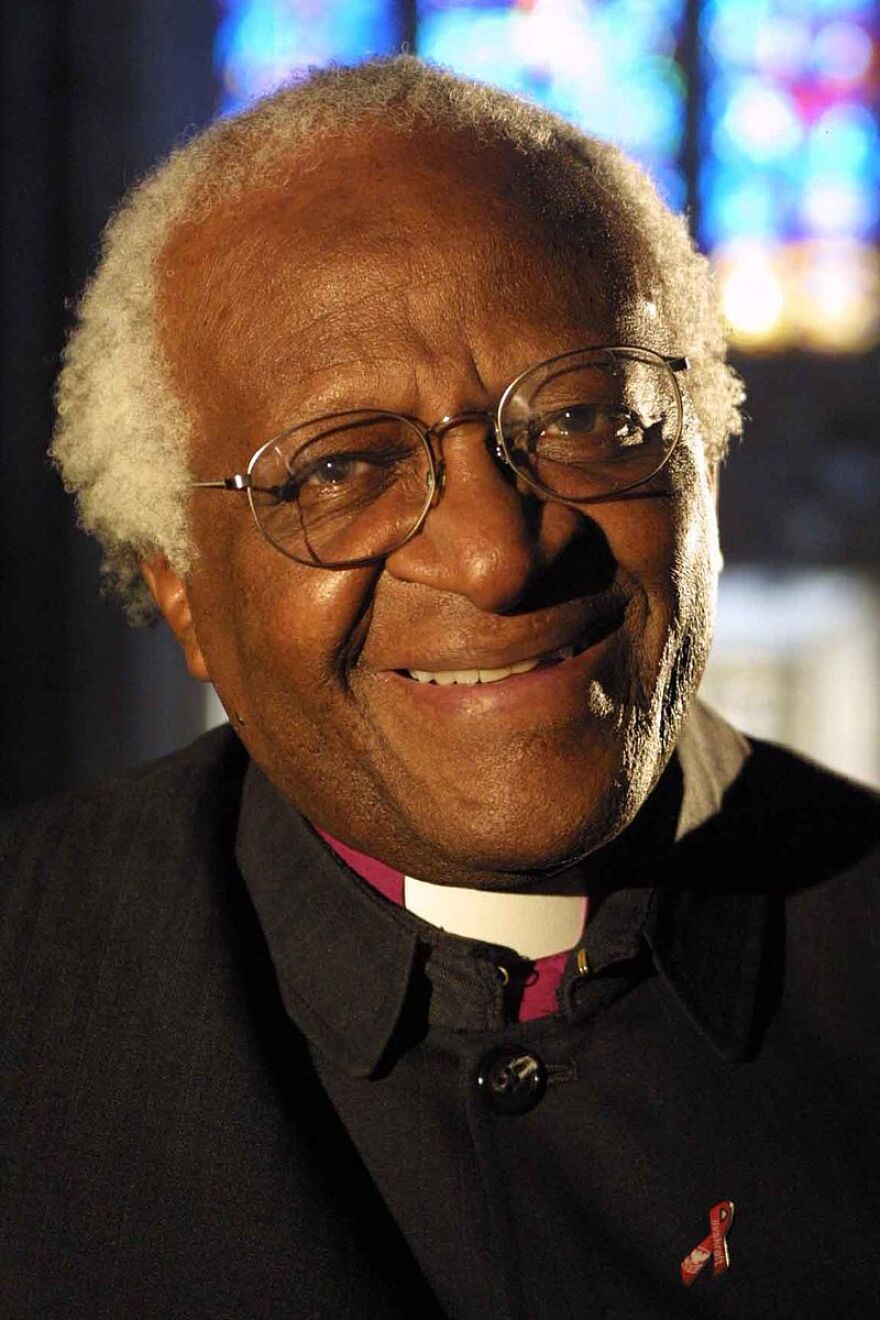

Oppressed South Africans were pursuing freedom, at great cost. Archbishop Tutu was a prominent voice of that struggle, blending his unshakeable faith, common sense, humanitarianism and determination.

The South African President P.W. Botha had given a racist speech the previous year, and had announced a national state of emergency in May 1986. He’d ordered air strikes against African National Congress bases in neighboring African countries.

In the United States, the Congressional Black Caucus was also engaged in exposing and dismantling the financial relationship between the U.S. and apartheid South Africa. They won the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act, which became public law in October 1986.

In the music world, Paul Simon’s project Graceland was released in the summer of 1986, and it focused the world’s attention on South Africa and its artists.

Tutu was first dreamed up as a collaboration between Miles Davis and Prince. The two had been sharing musical ideas for a while, and they belonged to the same record label. But Prince got caught up in his own career, and the project with Davis never materialized.

Marcus Miller had worked as a session bassist for Davis on Man With The Horn in 1981. Miller is also related to pianist Wynton Kelly, a mainstay of Davis’ '60s bands. Miller had already made a name for himself in both jazz and popular music, having worked with pianist McCoy Tyner, Luther Vandross, The Temptations and Grover Washington Jr.

The other compositions on Tutu were mostly composed by Miller, including an updated version of Davis’ 1956 “Half Nelson,” which turned into “Full Nelson,” a tribute to Nelson Mandela.

Tutu caused controversy among jazz purists for its use of electronics, funk rhythms and production values. But it was just what Davis needed for his final metamorphosis as a groundbreaking musician. Davis reportedly told Miller, “Thanks, man, you brought me back.” Davis died in 1991.

Vocalist Cassandra Wilson included a version of “Tutu,” which she'd renamed "Resurrection Blues," on her 1999 album Traveling Miles.

In 2006 guitarist George Benson and vocal wizard Al Jarreau released their album “Givin’ It Up,” which includes the song “ ’Long Come Tutu.”

In 2010, Miller went back into studio to make Tutu Revisited, featuring trumpeter Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah. “Whenever Miles played, you could hear all of his heritage in there,” Miller said in the 2012 interview. “You heard everything from the blues and gospel to Michael Jackson.” He felt that Scott had a similar style.

Music isn't the only way to honor Desmond Tutu. In his lifetime of speeches and writings, he left many instructions for improving your life and the world we all share:

“Differences are not intended to separate, to alienate. We are different precisely in order to realize our need of one another.”

“Do your little bit of good where you are; it's those little bits of good put together that overwhelm the world.”