It appears a pattern of heavy storms in the Pacific Northwest may have obscured the effects of climate change over the past 20 years. Researchers here have identified a southern shift in the jet stream as a source of heavy precipitation that built up snow pack and glacier mass in Washington and Oregon, while they were declining elsewhere.

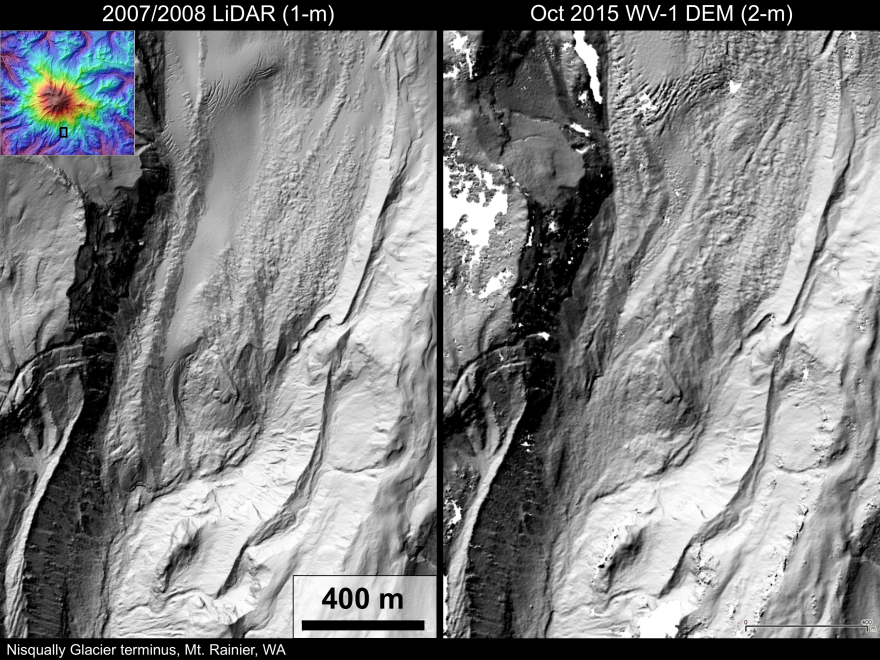

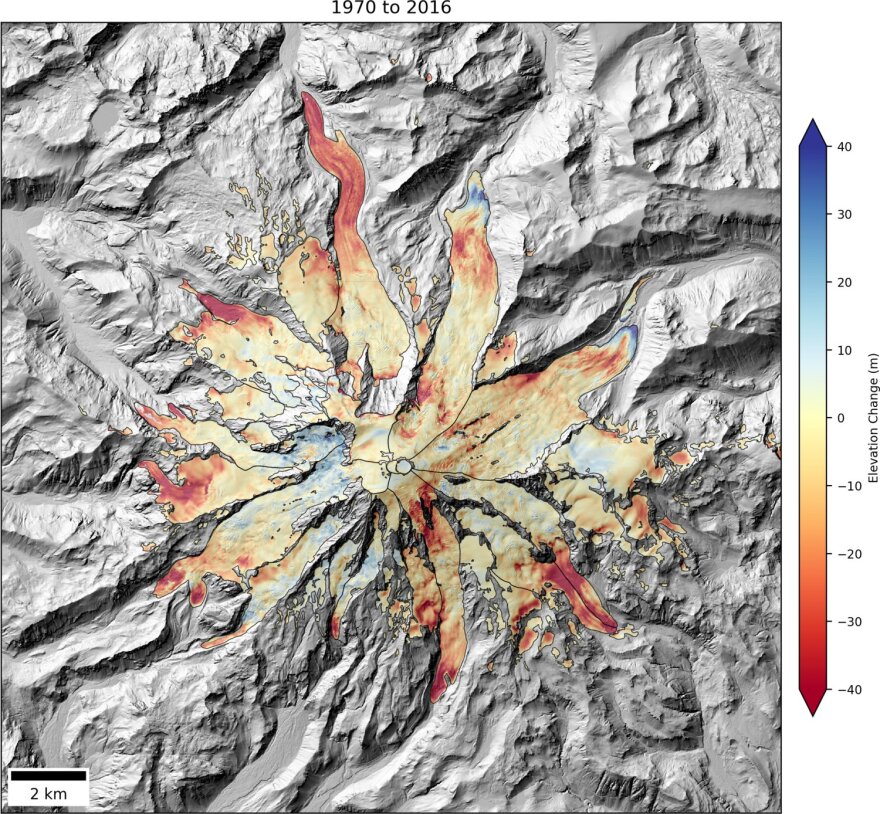

David Shean, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Washington, uses high-resolution satellite images to get precise measurements of glaciers and ice mass.

For a recent study, Shean teamed up with colleagues at the University of Northern British Columbia to assemble thousands of satellite pictures of North America's western glaciers. They mapped and modeled changes in the ice since 2000. Shean says they found a rapid increase in ice loss over the past 18 years overall, but less happening in the Pacific Northwest.

"It's actually relatively low, compared to some of the other mass losses that we’ve seen elsewhere in North America. So, it’s been a good 20 years, is one of the conclusions, for our glaciers here in Washington."

A different study out of Oregon State University linked that same phenomenon to preservation of mountain snow pack in the Western U.S. since the 1980s, despite the impacts of global warming. Nick Siler, the lead researcher on that study, told The Seattle Times he doesn’t expect that trend to continue.

“The climate-change signal masked over the last 35 years will become more clear,” Siler said.

When the jet stream shifts back to the north, warmer and drier weather would likely lead to declining snowpack and increasing glacial melt — both of which have big implications for water management affecting everything from drinking water and irrigation to fish health and hydropower generation.

Shean says this makes their work that much more important, though he admits his technique is still somewhat limited. The images it’s based on come from modern satellites and only have been available for a short span of time, starting around the year 2000. But the technology provides more accuracy and covers more ground than old methods that require field work in remote locations.

“It's giving us a much better handle on how our glaciers have changed in the last few decades and what that means in terms of water resources, in terms of sea-level rise. And it helps us better refine our models to allow us to make projections into the future for adapting to climate change."

Shean says next steps include finding ways to work with older images from spy satellites and aerial photography in the 1950s and 60s, to extend the record into the past.

His most recent study was published in the journal, Geophysical Research Letters.