This story is the first in a three-part series called "Who's Counted: Taking a Closer Look at School District Graduation Rates." The second and third stories will examine publicly funded online schools.

Jennifer Gonzales Salmeron struggled to feel happy during graduation season last year. While her friends prepared to accept their diplomas from Highline High School, the young woman with a bright smile stayed home with her newborn son, after dropping out in fall 2017.

“I felt really bad,” she said. “I felt like I disappointed my parents.”

Thinking about her son’s future, Gonzales Salmeron eventually realized she couldn’t give up on school.

“My son was my biggest motivation to return to school because I wanted to be a great example for him,” she said.

Returning to Highline would prove difficult because she was breastfeeding. So, a school counselor told her about the Learning Center, one of several dropout re-engagement programs offered by Highline Public Schools. The Learning Center offers students more flexible hours and online coursework; Gonzales Salmeron would complete hers while her son napped.

Eight months after enrolling, the 20-year-old has earned enough credits to graduate. She hopes to attend college to become a nurse or a medical assistant. Her success story is what lawmakers had in mind when they created Open Doors in 2010. The aim of the programs was to re-engage students between ages 16 and 21 who had dropped out, or help students who had fallen too far behind to graduate on time.

And yet, Gonzales Salmeron’s success in the program is the exception rather than the rule.

EXCLUDING DATA

Across the state, Open Doors programs have low graduation rates. Highline’s programs, for example, had an 11.3 percent graduation rate last year and a 47 percent dropout rate.

But because of a quirk in state policy, that low graduation rate isn’t factored in when the collective rate is calculated for Highline — a district that has recently posted dramatic increases in graduation rates.

“Graduation rate for the class of 2018 is over 81 percent,” Superintendent Susan Enfield said at an event in the fall, prompting applause from a crowd that included local politicians. “So this is the fifth straight year of us making steady gains in our graduation rate.”

Except that rate doesn’t include everyone from the 2018 class. About 200 students who attended Open Doors programs in Highline were excluded from the calculation. By excluding those students, who are most at risk of dropping out, Highline’s graduation rate got an artificial boost.

And Highline isn’t the only school district subject to the exclusions. It’s a statewide policy, set by the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction when the programs were first created.

While OSPI includes Open Doors students in the statewide graduation rate, they’ve been excluded from the Highline district count since the 2014-15 school year.

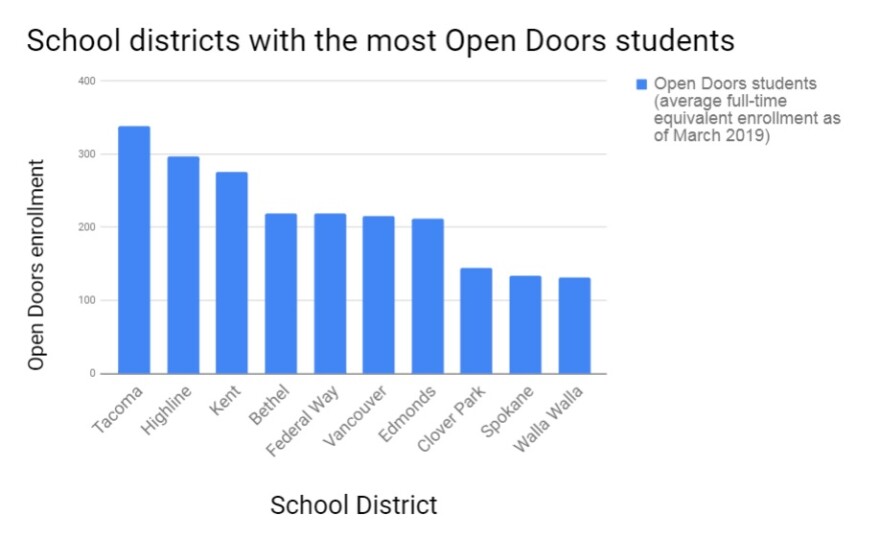

Some districts have a lot more Open Doors students than others. Tacoma Public Schools and Highline had the most students enrolled as of March, according to enrollment data from OSPI: 338 and 296, respectively.

GRAD RATES MATTER

The Highline district has taken a number of steps to help more students graduate, including changing discipline practices to reduce out-of-school suspensions, increasing the number of rigorous courses and trying to intervene early when students struggle.

There’s a lot riding on graduation rates — from superintendent compensation to home values. Under the No Child Left Behind law, schools with low graduation rates faced possible sanctions. The law’s replacement, known as the Every Student Succeeds Act, still emphasizes improving rates with a less punitive approach.

Underlying all of this attention to graduation rates is an acknowledgment that students who fail to finish high school will struggle to earn a living wage.

“There’s no doubt that the rates have gone up. Has Open Doors maybe increased that going up more? Perhaps,” Enfield told KNKX Public Radio. “But we’re very honest. We’ve always been very public about it. No one’s hiding anything.”

If Highline’s Open Doors students were included, last year’s graduation rate would have been 72 percent instead of 81 percent. But not all of those Open Doors students came from Highline schools — a spokeswoman said 42 percent of the most recent graduation cohort transferred from a different district to attend one of Highline’s re-engagement programs.

Nevertheless, it’s clear that dozens of vulnerable students from Highline schools aren’t tallied as part of the district graduation rate.

And critics say that renders them invisible.

‘THEY SHOULD COUNT’

Meg Van Wyk of Burien says she still closely follows Highline schools, even though her children graduated. The uptick in local graduation rates piqued her curiosity. “I started trying to figure out why,” she said.

It’s how she stumbled upon the OSPI policy that excludes certain students from district-level rates. Van Wyk says it troubles her. She wants to know if Open Doors students are really getting the wraparound services they need to succeed.

“They’re our most vulnerable students. They should count,” she said. “They’re just as important as the valedictorian at all of our graduations.”

OSPI officials say the approach was intended to encourage districts to re-engage these students, including young people from other districts. Deb Came, assistant superintendent for assessment and student information for OSPI, said her agency recognized a potential disincentive to re-engage those higher-risk students if district graduation rates were affected.

Still, the approach provides an incomplete picture. Came stressed that the data are available on individual Open Doors programs.

“The information is conveyed about the programs themselves,” she said. “So if someone wanted to see what’s happening at a particular re-engagement school, that information is available.”

OSPI is re-evaluating the policy. Came acknowledged there’s still work to be done: “Is the decision that was made several years ago still appropriate and should we do it differently?”

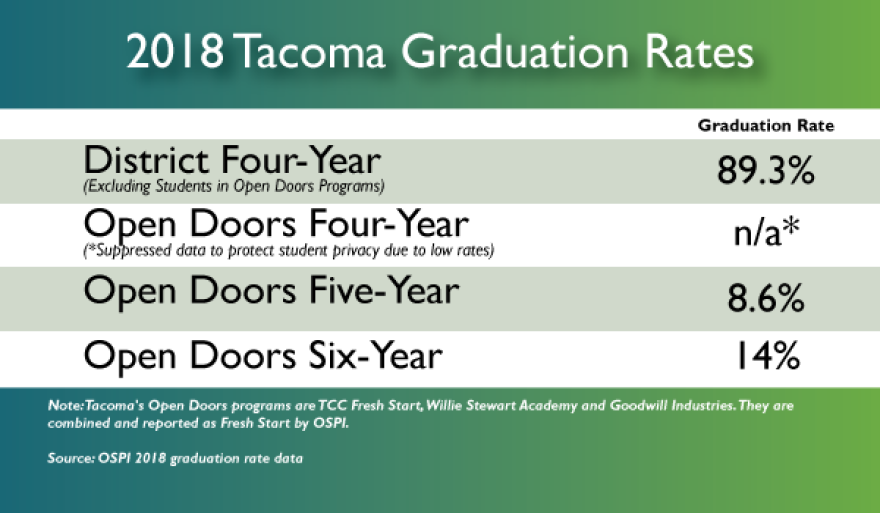

Some question whether the four-year graduation rate is the right way to measure success of this group of students since, by definition, they’re unlikely to graduate on time. But the five- and six-year rates are low, too.

For example, last year’s five-year rate for Highline Open Doors programs was 13.8 percent; the six-year rate was 19.2 percent.

In Tacoma, 8.6 percent of students in re-engagement programs were graduating in five years and 14.2 percent graduated in six. Tacoma’s district-level graduation rate was a record 89.3 percent last year, a milestone officials celebrated with a party complete with cookies frosted with “89.3%.”

But if Open Doors students had been included, it would have been 80 percent.

“Tacoma Public Schools explicitly follows the state’s prescribed calculation of graduation rate,” the district said in a statement. “We accurately report our graduation rate based on the state’s formula. We do not make up our own formula.”

OBSCURING COMPLETION RATES

Robert Balfanz says removing some students from the district-level calculations obscures completion rates. Balfanz, who directs the Everyone Graduates Center at the School of Education at Johns Hopkins University, co-authors an annual report on graduation rates.

He said the exclusions create a graduation rate “for the kids who we think with modest effort will graduate, as opposed to all our kids.”

Balfanz said dropout re-engagement schools should be held to higher standards — and they should be used as a last resort.

“You should take several attempts to try to support the kid before you decide they need to go somewhere else,” he said. “And if we create too many alternative schools, the temptation just gets too strong to say, for kids who are ready, they go here, for kids that aren’t, they go there.”

That’s exactly what two counselors and a teacher accused Tacoma’s Lincoln High School of doing in a whistleblower complaint in 2014. They said Lincoln was trying to move students to the district’s re-engagement center to improve its graduation rate.

After speaking publicly about their complaint, the employees were sued by the district. Officials argued the employees violated federal privacy laws by sharing student information with the media. The case ended with a settlement in 2017.

Tacoma Public Schools says the school acted ethically and appropriately. But one teacher, who wasn’t involved in the complaint, said the district’s decision to sue the educators amounted to retaliation. Superintendent Carla Santorno declined to be interviewed for this story.

In a written statement, the Tacoma school district said it takes steps above and beyond the criteria outlined in state law when considering whom to enroll at the district’s re-engagement center, Willie Stewart Academy.

For example, the school only takes students after they turn 17, even though the state allows 16-year-olds to enroll in Open Doors programs.

OVERCOMING OTHER BARRIERS

On a recent visit to Willie Stewart Academy, students described considerable obstacles they’ve faced and how the school has helped.

Janet Crutch, 18, said she struggled to fit in at Lincoln. She fell behind in her classes and, after a family member died, she quit attending.

“I was out of school, depressed, and didn’t know what to do,” she said. She searched for alternative schools online and found Willie Stewart Academy, where she’s in her second year.

Crutch said that while she won’t graduate with the students she originally started high school with, she’s likely to finish by the fall. Students are required to spend two and a half hours per day at the academy completing online classes.

“I like how teachers are welcoming,” she said. “They really care about your needs.”

Staff at the school even helped Crutch prepare paperwork to get an apartment, so she could leave what she described as a chaotic home life.

Tacoma Public Schools said about 10 percent of students who enroll at Willie Stewart Academy graduate. Crutch attributes the low graduation rate to problems students struggle with outside of school.

Many students in Open Doors programs contend with difficult living situations that make it hard to keep up in school. Some are homeless. Some have bounced around in foster care. More than 80 percent are low income, and many of them have experienced trauma.

“These are young people who need a different environment and are overcoming some pretty significant obstacles in life,” said Enfield, Highline’s superintendent. “So it’s not surprising that we see different numbers there.”

A new report by the state Education Research and Data Center found that 13 percent of Open Doors students earned a diploma two years after enrolling, while 46 percent dropped out.

PROGRAM DESIGN

But because the students have so many troubles outside of school, it's hard to know if that's why the re-engagement schools have such low graduation rates or whether it has anything to do with how the programs are structured. A good number of the schools rely on self-directed online learning. That hasn't worked for Desmond Thomas.

The 17-year-old moved a lot with his mom and attended high schools in Seattle, Tacoma and Kent before enrolling at Kent's Open Doors program, iGrad, last fall. But eventually, he stopped going.

He didn't connect with people, and didn’t understand why he was required to show up just to sit at a computer and complete online courses.

“In life right now, I basically feel like I’m just kind of bobbing in the water, not moving anywhere,” he said. “Just sitting there, sitting around in the waves.”

That's frustrating for his dad, Carlos Roland. He's trying to help his son get back on track and maybe earn a GED. Roland said he thinks Open Doors programs may work for self-motivated students. But they aren’t a good fit for kids like his son who need more structure.

“You hope they can say, ‘OK here’s what’s best for him, given his unique situation,’” Roland said. Instead, he says, the re-engagement program has a cookie-cutter approach that doesn’t work for students lacking internal drive.

Roland said school districts and the state need to figure out whether re-engagement programs are meeting students' needs. And, he said, he's concerned students like his son won't get the attention they need if districts can claim graduation-rate success while leaving out the most vulnerable kids.