At midnight 25 years ago, a ship called Exxon Valdez hit Bligh Reef in Alaska's Prince William Sound, spilling enough crude oil to fill 17 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

The event came as a shock to most people, but not to Kimbal Sundberg. He’d spent the three years leading up to that day mapping out what would happen in the case of just such an event.

As a habitat biologist for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Sundberg had commented on oil spill contingency plans for the state Department of Environmental Conservation. He'd even co-authored an impact analysis report on how an oil spill might affect fish and wildlife in the area.

When that experience actually unfolded three years later, Sundberg says the experience was "something like going to war."

Sundberg describes Prince William Sound before the spill as "pristine," with snow-capped mountains, forests, and seas, populated by puffins, sea lions, and orca whales.

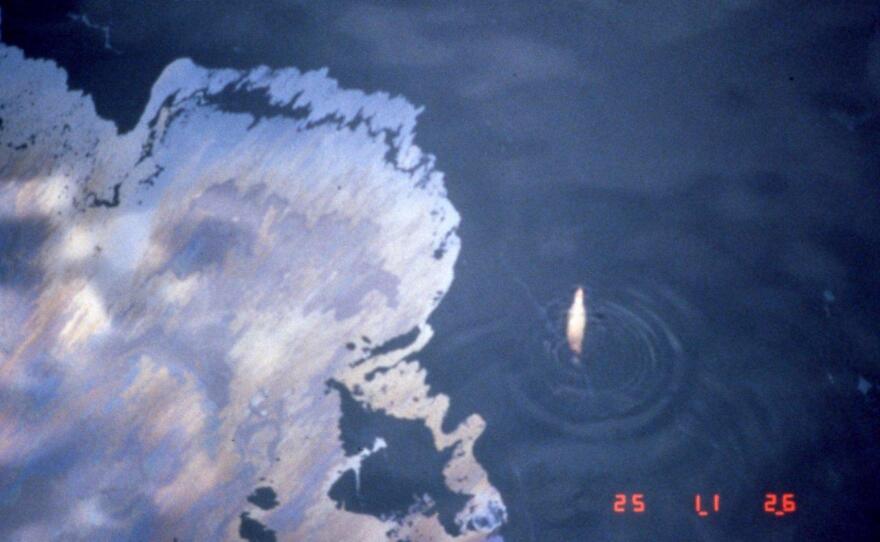

"When I got out there on March 25 with a helicopter, it looked like Los Angeles, like the kind of haze you get over Los Angeles," he said. "It was all the volatiles in the crude oil, which had boiled off and were like a smog layer over the top."

"It was dead calm," Sundberg recalled. "You could smell the petroleum in the air. Then the wind started to come up out of the north, and it blew 30 or 40 knots the next day. It took all that oil that was just in a gigantic slick around the tanker, blew it south, and spread it out over 1,200 miles of shoreline. Within a week, that oil had got pushed all the way down to Kodiak, and it was spreading all over the place. That was it.”

Sundberg and his colleagues immediately set to assessing damage to the wildlife, even getting down on their hands and knees to count individual barnacles and limpets that survived on coastal shores.

The Exxon Valdez disaster, the largest the U.S. had ever seen to date, took six months and a billion dollars to clean it up. Since then, bigger spills have eclipsed it. The 2010 Deepwater Horizon spill, for example, dumped 19 times more oil into the Gulf of Mexico. But while memories of the spill may have disintegrated, the oil itself hasn't.

"It’s now degrading at a rate of somewhere between zero to four percent per year," said Sundberg. "The scientists working on it now are saying that the Exxon Valdez oil may remain on some beaches in Prince William Sound and along the Gulf Coast for up to a century."

And while the ship itself has been dismantled, the potential for oil spills has hardly left Sundberg's mind, especially with looming proposals for new export terminals in the Pacific Northwest.

"My concern now is that we're talking about a whole different kind of oil here. I think our spill contingency plans are not up to snuff at this point with the new chemistry of these new products. They're not Alaska crude oil, which is what all our contingency plans are based on," said Sundberg.

"I'm really concerned that we're falling into this complacency again, thinking that we can become an oil exporting region without having a knowledge of what this oil is going to do if it spills into the environment here," he said. "It may sink to the bottom. We should know everything about what's going into these tankers on our marine waters, because we know that eventually there'll be another accident."

Saturday's oily mess in Galveston Bay, Texas, is one more reminder of that possibility.