Rae Akino’s work makes me uncomfortable; I’ve never been good with my own vulnerability. Her art reminds me of emotions I’ve pushed aside for far too long that need prioritizing.

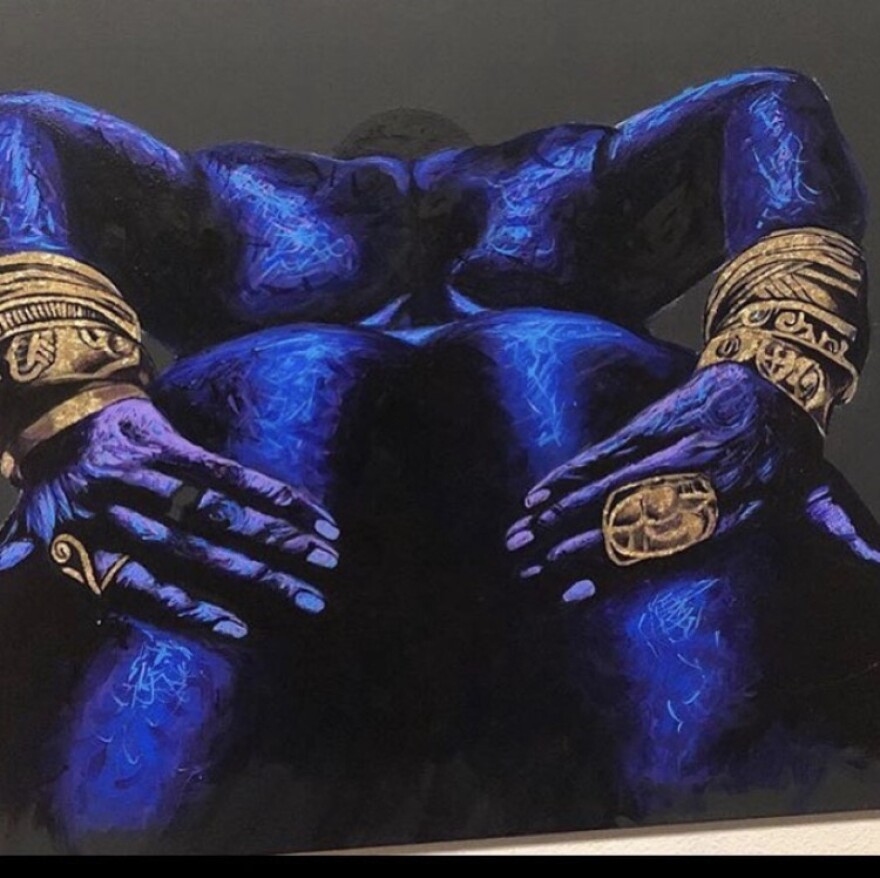

Like Akino’s painting of a person with blue Black skin that she’s named "Reclaiming Ourselves." A figure stands, hands placed with a delicate tension where I don’t think I’m allowed to describe in too much detail. (But this painting makes me wanna go into too much detail, especially during this quarantine where I feel that deeply exposed, equally vulnerable, and filled to my eyebrows with pandemic yearning: Akino’s work connects me to myself.)

In middle school, I remember being introduced to blue-black Black people through adolescent bullying absolutely rooted in colorism. Boys would decry the Blackness of beautiful dark-skinned girls. I remember being grateful that even though my dark skin earned me the nickname Blackie from my equally adolescent-minded and bullish biological father, my Black skin wasn’t the focus of their ire. The inviting, perhaps taunting, nature of Akino’s work in "Reclaiming Ourselves" reminds me of the constant bare-natured being of Black femmeness. The beauty of the casing and yet, often, the refused humanity unless we’re bare-naked prostrating ourselves with raw emotionality, often mistaken for Jezebelling. Even then, our humanity, mistaken for sexual invitation, commodified.

Akino’s artwork connects me to my Black community. In "Reclaiming Ourselves," she reminds me that this binary-less body is both gotten and responsible for dem pickney who need to get got. That artistic reminder is a 200-pound grown-ass human; feet stood backwards on my breasts, funky-smelling behind threatening above. That, like my responsibility to myself, makes me uncomfortable. It burdens me with my own self-care. It burdens me with my value. Seeing myself in both figures I see that I am integral inside Blackness.

I meet Akino via FaceTime. Her voice is kind and gravelly like the sound of the Harlem Renaissance that she loves. I can’t wait to ask Akino about her use of light. That’s the element that captivates me the most — how she uses light. She reveals that it’s how she sees color. That’s so cool!

Her piece "We Got Us" shows two seemingly genderless people: a hooded figure with a face that I’m sure I’ve made alone in the dark, holding the naked body of someone who’s unconscious. It’s how you cradle someone who’s too big to be held but must be held anyway. The held figure is Black, yes, but they have other colors on their skin. The colors aren’t bruises, but they remind me of being bruised. They remind me that I am both held and responsible for holding.

“Black women are always called on in a crisis and [are] there to put the pieces back together yet [are] left out of the story,” she says.

When I look at a piece of art like "We Got Us," I immediately want to leave the room and look at something else; that’s how much it jostles me. I think about the tendons of Blackness and their role in the sinew of my identity, especially during a time like this pandemic when systems of structural racism rely on the splintering of Blackness; I’m supposed to forget myself.

The strength depicted in this painting reminds me to relax my jaw and take inventory of my most tensed up places. Akino’s art reminds me of the somatic work I’ve been engaged in: embodying racialized trauma as a way to heal. How she sees and reveals color is a visual representation of sitting still and honoring the thin slices of ancestral memory in my tendons. She captures it.

I ask her, “How has your storytelling changed in the last eight months?” Selfishly, I need the advice. When Akino responds with, “I’ve become more vulnerable,” I am annoyed immediately because, of course: The artist whose work makes me uncomfortable is expressing the feeling that makes me most uncomfortable. She’s started to “work through her emotional barriers” and use them in her work. The story she’s telling “is related directly to her first. It’s become more intimate.”

Hoping for a fortune-telling, I tell Akino I am curious about how she sees her future unfolding. Did she have any projects on the horizon? She replies: “ 'Coloring Book for Black Adults' meant to be used as a tool for healing from this trauma. Having to go about my daily life with constant reminders [of this] is traumatizing...”

Akino wants the coloring book “to allow us to take a break from social media, from processing those emotions because we’re taught to put on our masks and go out into the world. We don’t have a space or a place to do that. We keep having the same conversations with each other. White people asking dumb questions. Just sit down. Take a breather. Color and you don’t slap nobody.”

OK, Rae, I won’t slap nobody, but when can I get my coloring book, though?

This story is part of the Artists Among Us series of profiles highlighting creatives around the region who are Black, Indigenous and People of Color. Jéhan Òsanyìn (they/them) is an artist, educator, activist and founder of Earthseed, where they use theater in wild spaces to decolonize those spaces and the bodies that pass through them.