If you came face to face with a great whale, you might find a few surprises in its chin: Like whiskers, if you look closely at the surface.

And, hidden inside the chin, lies a mysterious sensory organ, unknown to centuries of whalers and biologists.

You just need the right tools to find it: a high-tech, oversized x-ray machine, and the right saws to slice it into thin pieces that fit in a microscope.

A group of scientists based at the University of British Columbia, in Vancouver, BC, have done all that looking—and they discovered an organ that serves a crucial purpose and answers a longstanding mystery.

Here is a graphic from the science study, published in Nature (expand the graphic to full screen to for best browsing of the information and images):

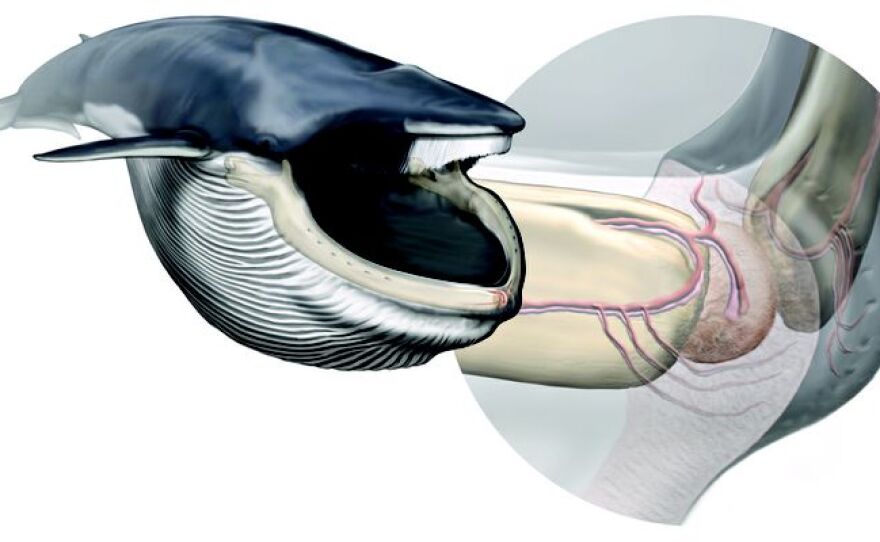

How do great whales, such as humpbacks and blues, drive their jaws so wide open and then snap them shut, while swimming at full speed?

“These heads are five meters long and weigh close to ten tons,” says Nick Pyenson, first author of the new study, published in the journal Nature. He’s now the curator of fossil marine mammals at the Smithsonian Institution.

“What we found in the course of our investigation into the jaw and skull anatomy was this surprising structure in the chin. We had no idea what it was.”

The researchers decided it’s a sensory organ, based on the types of tissue they found, and the way the nerves run into it, and then to the whale’s brain.

“The kind of nervous tissue that’s linked up to that structure in the chin is derived from the sensory nervous system," says Pyenson. “We think its function is to relay information about the position of the jaw during the course of the lunge.”

This sensory organ is in whales that feed by lunging at schools of krill or other tiny sea creatures, with their jaws gaping. This group is called rorquals, and also includes minke, fin and other species. They sift a mouthful of water through their baleen teeth. It’s a finely orchestrated hunting maneuver, where the jaw and throat do most of the work.

A BBC video of the big gulp happening:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bCH3TXq6VG8&feature=plcp

Dramatic triple-jointed jaw

“When they feed, it’s a dramatic event,” says Jeremy Goldbogen, another marine mammal expert on the research team. He’s now with Cascadia Research Collective in Olympia, Wash. “The jaws rotate dramatically, and the chin deforms.”

The jaws of these whales have three joints. You and I have just two, but the whales have a joint at the tip of the chin.

And stretching from the chin all the way to their navel is a flexible throat.

Here’s how the whale feeds, according to Pyenson: It swims full-speed, and when the sensory organ sends the right signal, it suddenly swings its lower jaw wide open, using the triple-joint to spread cartoonishly large. The open jaw acts like a parachute on a drag-racer, bringing it to a stop in under ten seconds. By now, the throat has ballooned big enough to nearly double the whale’s size with tons of sea-water.

At this crucial instant, that same sensory organ signals that it’s time to twist the body and snap the jaw shut, before the tiny sea creatures can escape.

Here is a National Geographic video focusing on how Northwest researcher John Calambokidis of Olympia is trying to record whales, attempting to attach a camera to one:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lO4Q9JJrVq0

Humans have similar nerves

“It’s a new sense organ, but it’s not a new sense,” because most mammals have similar nerves, mechanoreceptors and proprioreceptors, says Joy Reidenberg, a specialist in comparative anatomy at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. She was not involved in the whale research.

“It’s that ability to detect, without even looking, whether your elbow is folded or your elbow is extended out. You can tell just by the stretch receptors inside the muscle. Or, if you take your lip and you pull it down, you can feel it stretch, too.”

The sensation of stretching for humans often registers as pain, but “this isn’t painful for these animals because they're adapted to be able to expand their jaw in this interesting way,” she says.

"Is it really a new organ? Probably," says Reidenberg, "because it’s a dedicated tissue to just this one sensation."

Pyenson has not yet given the new organ a name.

“The discovery of this organ raises questions about its role in the evolution of lunge feeding in whales,” the authors write in their Nature article. They speculate the organ evolved when whales were much smaller marine mammals, 20-30 million years ago, and that having this sensory organ may have been a prerequisite for growing so enormous.

And, as for those whiskers on the chin – they also appear connected to the sensory organ and probably play a role in sensing when to fling the jaw wide open.

This BBC video really shows how the mouth and throat open wide:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fOMzFFh3rEA